About Alzheimer’s Disease

What is Alzheimer's Disease (AD)?

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia. Approximately 6.7 million people in the United States currently have Alzheimer’s disease, and the aging "baby boomer" population is expected to make this number increase markedly. Alzheimer’s disease prevalence increases with age. About 5 percent of people between the ages of 65 and 74 and about 33% of people over the age of 85 have Alzheimer's disease.

What are the Symptoms of Alzheimer's Disease?

Alzheimer's disease typically begins with memory problems such as forgetting recent events or conversations. However, it can also manifest with language deficits (for example, difficulty with word-finding), visual-spatial deficits (for example, difficulty navigating or interpreting things that are seen), or as personality changes such as increasing social withdrawal and loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities. Problems such as managing one's finances and difficulty driving can occur relatively early in the illness. As the disease progresses, anxiety, frustration, and suspicion can occur. Sometimes delusional thoughts and agitated behavior occur. Persons affected by Alzheimer's disease increasingly lose their independent functioning and eventually become unable to perform basic activities such as dressing and bathing.

What Causes Alzheimer's Disease?

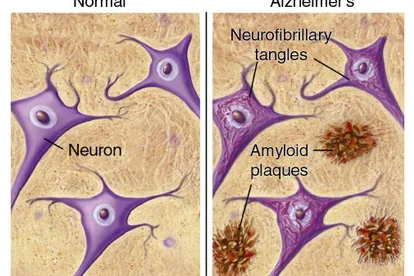

The symptoms of Alzheimer's disease are caused by progressive loss of brain cells, or neurons, and the connections between them. Along with a decreased number of neurons, the brains of persons with Alzheimer's disease show neurofibrillary tangles, or abnormal forms of protein deposits in neurons. Also present in an Alzheimer's brain are amyloid plaques, clumps of extracellular proteins that are thought to be the initiating cause of the disease. Though the causes of Alzheimer's disease are still incompletely understood, the abnormal processing of the amyloid protein due to factors associated with aging or specific genetic alterations are thought to play important roles.

Genetics

The genetics of sporadic Alzheimer's disease are complicated and only partly understood. Rare cases of highly genetic forms of Alzheimer's disease in which 50% of the members of a family get it at a young age (typically between ages 30 and 60) are caused by alterations in one of three genes called Presenilin 1, Presenilin 2 and the Amyloid Precursor Protein gene. An additional gene, apolipoprotein E (APOE) has also been characterized as a genetic risk factor for Alzheimer's disease. One form of the ApoE gene – ApoE4, present in 10-15% of Caucasians, increases one's risk of late-onset disease. Many other candidate genes are being identified.

Cognitive Reserve

It is well-documented that some people who show extensive Alzheimer changes in their brain on autopsy have demonstrated no symptoms of Alzheimer's disease during life. In addition, persons with mild symptoms and persons with more severe symptoms may show similar amount of Alzheimer's disease pathology in the brain suggesting that there are other factors that influence the relationship between the severity of Alzheimer's disease brain pathology and clinical symptoms. Studies suggest that having a lower level of education or decreased occupational attainment increase one's risk of developing Alzheimer's disease. Though whether these factors actually increase the likelihood of the development of plaques and tangles or neuron loss is controversial, these factors do seem to increase the likelihood with which one will be diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease. In other words, restricted educational opportunities may lead to a decreased ability of one to ward off the effects of Alzheimer's disease pathology (i.e. reduced "cognitive reserve"). It stands to reason therefore that engaging in activities that are good for the brain (e.g. eating a balanced diet, exercise, staying mentally active) and avoiding activities that are bad for the brain (e.g. drug abuse, head trauma) would decrease one's risk of exhibiting the symptoms of Alzheimer's disease.

Risk Factors

Large epidemiologic studies have suggested that a variety of risk factors that increase or decrease one’s risk for Alzheimer's disease exist. For example, the E4 variant of the APOE gene increases one's risk for Alzheimer's disease. This does not mean that they will definitely get Alzheimer's disease. Rather, relative to someone who does not have that variant, they are at higher risk. A large number of additional genetic risk factors have been identified more recently, but all have a smaller effect on disease risk than does APOE E4. The most well-replicated risk factor for Alzheimer's disease is age. The older we all get, the higher our risk for Alzheimer's disease but not every elderly person will get it. Among the findings from large epidemiologic studies, many factors have been shown to increase one's risk for Alzheimer's disease.

These include:

-

Age

-

APOE e4 genotype

-

Family history of Alzheimer’s disease

-

Diabetes

-

Strokes

-

Cardiovascular disease

-

Head trauma

Alternatively, a number of factors have similarly been shown to decrease one's risk for Alzheimer's disease:

-

Exercise

-

Education

-

Social activity

-

Mental activity

-

Diet (fish, dark green leafy vegetables, antioxidants, etc)

The Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)

Alzheimer's disease can be diagnosed with complete accuracy only after death, when microscopic examination of the brain reveals plaques and tangles. However, based on the following techniques, doctors can usually diagnose it clinically with up to 90% accuracy.

Lab Tests

Blood tests are performed to rule out other causes of the dementia, such as thyroid disorders or vitamin deficiencies.

Neuropsychological Testing

Sometimes it is useful to carefully evaluate the specific degree of deficits in memory and thinking in order to determine the likelihood with which it represents a neurological disease. This type of paper-and-pencil testing may take hours to complete and gives doctors a detailed understanding of one's intellectual strengths and weaknesses.

Brain Scans

-

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or Computerized Tomography (CT)

A brain MRI or CT provides a detailed view of the structure of the brain and allows doctors to identify other neurological diseases (stroke, tumor, hydrocephalus) that may be contributing to or causing the cognitive symptoms. It can sometimes reveal patterns of brain atrophy, or shrinkage, that are characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease or other causes of dementia.

In addition, PET technology can now be used to directly detect the amyloid plaques in brain which are known to accumulate early in the course of the illness. Though not yet consistently covered by insurance, this "amyloid imaging" is now available for use in the clinic.

-

Positron Emission Tomography (PET).

In FDG-PET scans, patients are injected with a small dose of radioactively labeled glucose. They are sometimes performed to identify patterns of decreased metabolism (glucose uptake) characteristic of Alzheimer's disease or other forms of dementia.

Medical Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease (AD)

Though we currently have no cure for Alzheimer's disease, two classes of drugs are available that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

Cholinesterase Inhibitors

This group of medications, consisting of donepezil (Aricept), rivastigmine (Exelon) and galantamine (Razadyne), works by increasing the level of a certain chemical messenger in the brain. Clinical studies have confirmed that treatment with these agents results in improved cognitive function, relative to placebo. They are generally safe though reversible side effects like diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting can occur. Among these agents, donepezil has been approved by the FDA in mild, moderate, and severe Alzheimer's disease. Rivastigmine and galantamine are approved in mild and moderate Alzheimer's disease. Rivastigmine has recently become available in a transdermal patch.

Memantine (Namenda)

Though the exact way by which memantine exerts it's effect in Alzheimer's disease is not entirely clear, it has been shown that persons with AD, particularly those in the moderate to severe stage of the illness, do better in regards to tests of thinking and in overall function over time than those not treated with the drug. As it is thought to have a different mechanism of action than do the cholinesterase inhibitors, memantine is often used in combination with this class of agents. Concomitant therapy with both memantine and a cholinesterase inhibitor may have added benefit.

Other Symptomatic Treatments

It is sometimes necessary to prescribe drugs for symptoms that may accompany Alzheimer's disease such as sleeplessness, wandering, anxiety, agitation, psychosis, and depression. You should talk to your doctor if you or your loved one has Alzheimer's disease and you believe that you need these or any other medication.

Caring for Persons with Alzheimer's Disease in the Long Run

Over years, persons with Alzheimer's disease become increasingly dependent on others for their basic needs. In time, persons with AD become unable to dress, bathe, and use the toilet and ultimately become unable to walk and eat. This can lead to tremendous stress on both patients and their caregivers. There are many challenges that confront caregivers at different stages as the disease progresses. There are helpful books and support groups available that provide the opportunity to learn important caregiver strategies. Contact your local Alzheimer's Association affiliate or another community partner to get connected with such support groups, doctors, resources and referrals, home care agencies, supervised living facilities, a telephone help line, and educational seminars. It is important to find ways to take time off to attend to one's own health (for example, explore the availability of adult day care programs).

Rare, Focal Variants of Early-Onset Alzheimer's Disease

The affiliated Behavioral Neurology Program specializes not only in FTD and non-Alzheimer dementias, but also in unusual and rare, focal variants of Alzheimer’s disease. These include Posterior Cortical Atrophy, logopenic progressive aphasia, “frontal” Alzheimer’s, and others. Most people think of Alzheimer’s disease as involving elderly individuals with memory difficulty and are not aware of young-onset (40’s to early 60’s) presentations with inability to see properly (Posterior Cortical Atrophy), difficulty finding words (logopenic Progressive Aphasia), or alterations in judgment (behavioral/dysexecutive variant). The Behavioral Neurology Program has one of the few NIH funded programs that studies these rare, focal variants of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Understanding these patients and the different brain networks involved helps us understand what causes all types of Alzheimer’s disease.